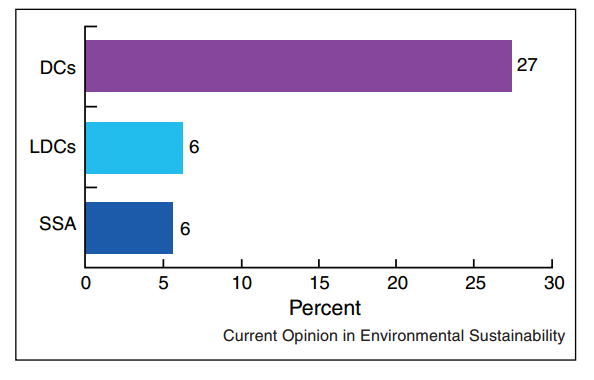

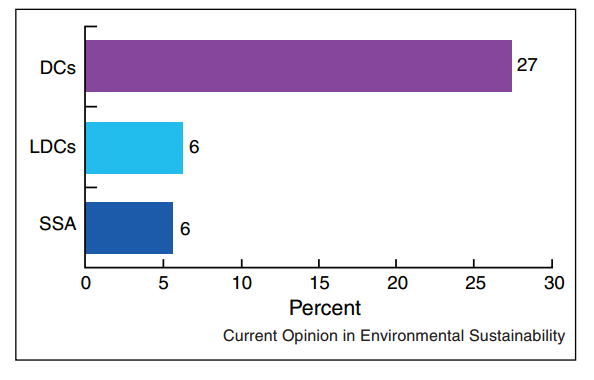

Clean cookstoves, also known as improved cookstoves (ICS) have the potential to significantly change patterns of household and institutional energy use in developing countries. However, access to clean cookstoves for consumers in developing countries remains low, despite high levels of fuel use appropriate to cookstoves being prevalent in developing countries, particularly in rural areas.

Share of population using solid fuels with access to improved cookstoves in Developed Countries (DCs), Least Developed Countries (LDCs) and Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) [1]

The use of clean cookstoves has the potential to improve livelihoods, particularly for women and children, in developing countries through alleviating the time burden of gathering fuel, allowing users to spend more of their time on other activities, for example income generation. Daily collection of firewood for cooking can vary in duration from 3 hours [7] to seven hours [8]. Clean cookstove technologies such as rocket stoves can achieve the same cooking results, in the same time, while using just 60% of the fuel [8]. Global Alliance for Clean Cookstoves research has shown that traditional cookstove-using households in India, Bangladesh and Nepal on average spend 660 hours/year on fuelwood collection, while improved cookstove households spend just 539 hours/year [9]. Indoor air quality improvements are another key benefit. Around 3.8 million premature deaths annually are caused by non-communicable diseases, such as heart diseases and lung cancer that can be attributed to indoor air pollution [3].

Removing poorly-combusting, high-smoke fuels such as traditional wood fuels from the household energy mix in developing countries, and reducing indoor air pollution consequently, would have huge positive consequences for public health in the developing world.

Clean cookstoves technologies tend to be demarcated on the type of fuel used, as well as the general design of the cookstove and its technological aims. These cookstoves can also be demarcated through cost, with lower-cost cookstoves made from clay or metal with a clay lining, and higher-cost stoves using factory-machined materials like metals. Differences in cost tend to lead to different target market, with low-cost cookstoves targeting rural consumers, and higher-cost cookstoves focusing on emerging middle classes and high-income employees. Costs for a household clean cookstove can range from US$10 to US$350+, and as such different business models are required to disseminate these stoves to best reach their target markets. High-cost stoves are most commonly directly sold to consumers, whereas low-cost stoves can be available through government or donor programs of dissemination, as well as through direct purchase, vendor-credit or micro-credit models. [4] [6]

Stovetech combined wood/charcoal improved cookstove. Source: http://inhabitat.com/four-cooking-stove-designs-that-can-save-the-world/

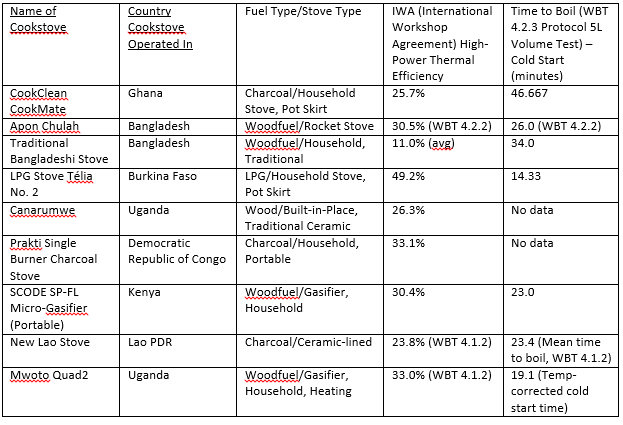

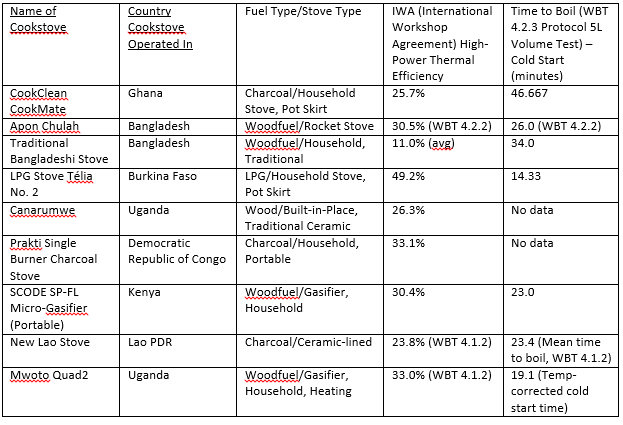

Solid fuel cookstoves, for example cookstoves using traditional woodfuels, tend to aim for significantly more efficient combustion of fuels, reducing indoor air pollution in the form of smoke and particulate matter, as well as generating more heat. These efficient designs can focus on combusting fuel more effectively, through designing combustion chambers to allow for more aerobic combustion, whereas others focus on having a heavily-insulated cooking chamber to reduce heat loss, focusing on longer cooking times for the same amount of fuel. Other cookstove designs for developing countries focus on using more efficient fuels with low-cost technology. Some examples of this include efficient charcoal stoves, as well as LPG stoves designed for developing country use.

Lab efficiencies of various established cookstove designs used in the developing world. Table established by D. Kerr derived from http://catalog.cleancookstoves.org/test-results, with standards available online at: http://cleancookstoves.org/technology-and-fuels/testing/protocols.html

However, lab efficiencies do not always translate into real-world efficiencies. A recent Indian cookstoves study conducted by researchers at the University of Washington and the University of British Colombia found disparities in real-world use efficiencies in a recent CDM program of cookstove dissemination from the Indian government. Particulate matter emissions especially were higher than expected, which may have been due to the ‘stove-stacking’ phenomenon, where families continue to use traditional cookstoves after receiving an improved cookstove. Some 40% of households in this study were found to be doing this [5].

Dissemination of clean cookstoves, and growth in access to the technologies, has the potential to have a significant positive impact on the sustainability of energy use and improvement of livelihoods of consumers in developing countries. Whilst state-run programs have had some success in directly distributing clean cookstoves, market-based measures have been shown to have significant impacts over the medium-long term, and private cookstove markets have developed in a number of Sub-Saharan African countries, such as Kenya, South Africa and Uganda. Markets across the world have disseminated large numbers of cookstoves, with over 12 million disseminated in China in the 2012-2014 period, 4.5 million in Ethiopia, and nearly 3 million in Cambodia [12]. The Kenyan clean cookstoves market was sized at 2,565,954 units in 2012, with high levels of urban and peri-urban penetration (~35%), but significantly less rural coverage [10]. The Ugandan market by comparison is estimated to be around 600,000 households, with urban areas again dominating this group [11].

This series of posts aims to explore the variety of models that private businesses can use to achieve scale and sustainability in their operations in the clean cookstoves sector [2]. Direct dissemination will be compared to vendor purchase, vendor credit and micro-credit models in the second blog of this series. Post three will explore the clean cookstoves value chain and identify opportunities for business growth along the value chain, and the fourth post in this series will examine the role of government in promoting clean cookstoves businesses.

– Daniel Kerr, UCL Energy Institute

[1] Bazilian et al. (2011) Partnerships for access to modern cooking fuels and technologies. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, Vol. 3, pp. 254 – 259.

[2] Rai & McDonald, GVEP International (2009) Cookstoves and markets: experiences, successes and opportunities. Available at: http://www.hedon.info/docs/GVEP_Markets_and_Cookstoves__.pdf

[3] WHO Website (2016) Household air pollution and health. Available at: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs292/en/

[4] Global Alliance for Clean Cookstoves (2016) Clean Cooking Catalog. Available at: http://catalog.cleancookstoves.org/stoves

[5] University of Washington (2016) Carbon-financed cookstove fails to deliver hoped-for benefits in the field. Available at: http://www.washington.edu/news/2016/07/27/carbon-financed-cookstove-fails-to-deliver-hoped-for-benefits-in-the-field/

[6] Global Alliance for Clean Cookstoves (2016) Business and Financing Models., Available at: http://carbonfinanceforcookstoves.org/implementation/cookstove-value-chain/business-models/

[7] FAO (2015) Running out of time: The reduction of women’s work burden in agricultural production. Available at: http://www.fao.org/3/a-i4741e.pdf

[8] GACC (2015) The Use of Behaviour Change Techniques in Clean Cooking Interventions to Achieve Health, Economic and Environmental Impact. Available at: https://cleancookstoves.org/binary-data/RESOURCE/file/000/000/369-1.pdf

[9] GACC/Practical Action (2014) Gender and Livelihoods Impacts of Clean Cookstoves in South Asia. Available at: https://cleancookstoves.org/binary-data/RESOURCE/file/000/000/357-1.pdf

[10] GVEP/GACC (2012) Kenya Market Assessment: Sector Mapping. Available at: https://cleancookstoves.org/binary-data/RESOURCE/file/000/000/166-1.pdf

[11] GVEP/GACC (2012) Uganda Market Assessment: Sector Mapping. Available at: http://cleancookstoves.org/resources_files/uganda-market-assessment-mapping.pdf

[12] REN21 (2016) Renewables Global Status Report. Available at: http://www.ren21.net/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/GSR_2016_Full_Report_REN21.pdf